Last week, I compiled a

list of books which have had the most significant impact on my life and worldview. Like many bibliophiles, a large portion of how I interact with and understand the world has been shaped by what I've read. But reading is only a part of the whole picture, and if picture is worth a thousand words, than any graphic novel is worth at least a dozen books. The image can convey many things that the written word alone cannot, and when the two modes of expression work in tandem, marvelous things can happen.

I would like to present you,

Gentle Dear Reader, a few of the graphic novels (and one comic strip) which have had the greatest influence on my worldview, more-or-less in the order in which I first encountered them.

Which comic books would be on your personal list of the most meaningful graphic novels you've ever read? Leave your list below in the comments!

1) Calvin and Hobbes, by Bill Watterson

“Hold it. You know what I'd like to see? I'd like to see the three

bears eat the three little pigs, and then the bears join up with the big

bad wolf and eat Goldilocks and Little Red Riding Hood! Tell me a story

like that

, OK?”

― Calvin

These comics are among the first things I remember reading as a child. To my mind,

Calvin and Hobbes is without question the single greatest body of sequential art ever assembled. By turns philosophical, hilarious, poignant, and incisively witty, six-year-old Calvin and his tiger-friend Hobbes informed a great deal of how I spent my time as a child. Like Calvin, I was possessed by a great love of nature and exploration, and he inspired me to make many unsupervised trips through forests and go mucking my way along creek-beds, looking for whatever "weird stuff" I might be lucky enough to find.

I also inherited Calvin's disinterest in organized sports (which I carry to this day, though not as fervently as I used to), his love of unstructured learning, and the joy he took in noticing the beautiful details which grown-ups miss.

2) Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, by Scott McCloud

"Space does for comics what time does for film!"

― Scott McCloud

Unfortunately, one of the views that I absorbed from

Calvin and Hobbes was Mr. Watterson's disdain for comic books and graphic novels, which he called "incredibly stupid" (which I feel is a little hypocritical of him, since he wrote comics which were eventually collected and sold in book-format, but that's beside the point).Luckily for me, I stumbled upon a copy of Mr. McCloud's excellent book in the bookstore at Eastern Michigan University, and he immediately blew my mind clear out of the water.

Understanding Comics taught me to reconsider art forms that I had previously written-off, like rap and modern art. It taught me not to confuse the medium with the message: just because comic books have historically been the domain of cheap, badly-written, easily-disposable kiddie fare doesn't mean that all of them

have to be, all of the time. What if people had persisted in believing, as they did in Shakespeare's day, that theater could never be anything more than a cheap, frivolous distraction for the lower classes? Imagine how much poorer the world would be today, as a result of their shortsightedness.

3) Maus: A Survivor's Tale, by Art Spiegelman

“Friends? Your friends

? If you lock them together in a room with no food

for a week…Then

you could see what it is, friends!"

― Vladek Spiegelman, to his son Artie (age 11)

Maus is an oddity, and not just because it's a Holocaust narrative in comic book format, or because it's a Holocaust narrative starring cartoon animals (Jews are mice, Nazis are cats). It's also the most unsentimentally honest portrayals of a father that I've ever read. Despite living through one of the most horrific examples of institutionalized racism in human history, the Vladek Spiegelman is still intensely prejudiced against African-Americans; he's emotionally manipulative of his son, wife, and daughter-in-law; he's a tight-fisted cheapskate; he dismisses the feelings and concerns of those closest to him; and he constantly comparing his second wife unfavorably to his first wife (the author's dead mother). In a weird way, all this behavior this makes Vladek intensely... human, I suppose. Filled with all-too-human shortcomings and weaknesses. We can't all be Anne Frank,

believing, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart. Suffering does not necessarily make one more compassionate towards one's fellow sufferers.

3) Watchmen, by Alan Moore (illustrated by Dave Gibbons)

“There is no future. There is no past. Do you see? Time is simultaneous,

an intricately structured jewel that humans insist on viewing one edge

at a time, when the whole design is visible in every facet.”

Calling

Watchmen "mind-blowing" doesn't do the book justice. That's barely scratching the surface of what this novel is, of what it does. Every single time I read this book, I stumble across some new insight, some new interpretation of the characters, their motivations, their inner workings. In eschewing the self-narrating

thought bubbles of past comics artists, Alan Moore forces the reader to delve deep into complex and messy psychologies of these "real-world" superheroes, and the mechanisms which drive them to spend their nights dressing up in kinky, colorful skintight costumes and beating the stuffing out of petty criminals (which, if you think about it, is more than a little weird).

Moore also does an excellent job of pointing out that beating up random lawbreakers isn't going to solve anybody's problems in the long run. When

Ozymandias (the self-styled"smartest man in the world") proposes taking action against a recurring villain who has just returned from prison, a bitter and cynical hero called The Comedian turns his acidic tongue on his fellow heroes, pointing out how ultimately pointless their nocturnal beatdowns are, in a world living in the looming shadow of the Cold War:

"You people are a joke. You hear Moloch's back in town, you think "Oh, boy! Let's gang up and bust him!" You think that matters? You think that solves anything? ... It don't matter squat because inside thirty years the nukes are gonna be flyin' like maybugs...and then Ozzy here is gonna be the smartest man on the cinder."

4) V for Vendetta, by Alan Moore (illustrated by David Lloyd)

"You're in a prison, Evey. You were born in a prison. You've been in a prison so long, you no longer believe there's a world outside. That's because you're afraid, Evey. You're afraid because you can feel freedom closing in upon you. You're afraid because freedom is terrifying. Don't back away from it, Evey. ... You faced the fear of your own death and you were calm and still. The door of the cage is open, Evey. All that you feel is the wind from outside.”

― the anarchist known as "V"

I can't say that I

agree with Alan Moore's politics, but they certainly make for thought-provoking reading material. I've never really read a coherent, well thought-out argument in favor of anarchy before or since, and some of the points that he brings up are pretty good ones. Governments always involve a loss of freedom on many levels, but these bodies to whom we hand over our liberties frequently do not have our best interests at heart. They're made of humans, who have their own interests at heart, as all humans inherently do. We tell ourselves that it's for our own good, that the alternative to government is chaos, etc., but ultimately, we're

all free, all of the time, to do whatever we want. Most of us just choose not to, out of fear, uncertainty, the implicit or explicit threat of violence against our bodies and our families, etc. But the world only works that way because we

allow it work that way.

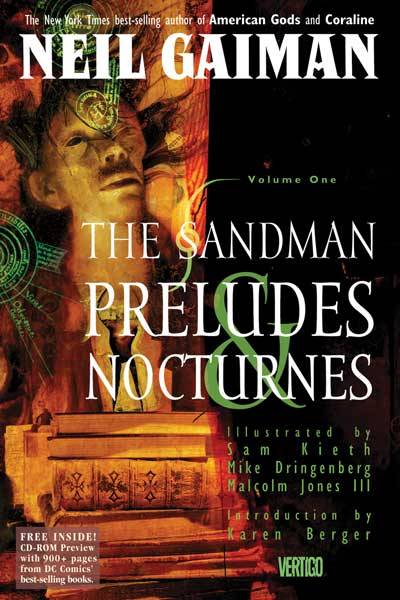

5) The Sandman, by Neil Gaiman (illustrated by various artists)

“Everybody has a secret world inside of them. All of the people in the whole world. I mean everybody. No matter how dull and boring they are on the outside, inside them they've all got unimaginable, magnificent, wonderful, stupid, amazing worlds. Not just one world. Hundreds of them. Thousands, maybe.”

― Barbie (a.k.a. Princess Barbara), "A Game of You"

What can I even say about this series? It might be the best thing I've ever read, in any medium. And that's

really saying something, considering how much I've read in my life.

For the first few chapters,

The Sandman is a pretty standard horror comic about Morpheus, the King of Dreams, trying to regain his kingdom after seventy years' imprisonment in the mortal realm. It's good; spooky and atmospheric, but not

great; not yet. Not until the last chapter of the first volume, when Gaiman introduces

the most endearing personification of Death herself that's ever been penned, and then shit starts to get

weird (in the best possible way). Jumping between the Dreaming, the "real" world, the

skerries of dream, Heaven, Hell, Limbo, Faerie, the Underworld, various historical pantheons (both real and invented, ancient and modern), and an innumerable host of stories,

The Sandman is a shifting, shimmering phantasmagoria of images, words, and complete self-contained universes, each one stranger and more sublime than the last. Reading this series will forever alter the reader, because it forces one to question the nature of reality, time, of the primal power of storytelling to (sometimes literally) reshape one's world.

It is

damn good stuff. You should go read it. Right now.

6) Scott Pilgrim, by Bryan Lee O’Malley

“I feel like im in this river just getting swept along... And if I hold on to anyone, if I'm holding on for dear life, I'm not getting anywhere. I'm stuck. ...I never wanted to get stuck.”

―Scott Pilgrim, Scott Pilgrim's Finest Hour

Scott Pilgrim is a coming-of-age novel for the

Nintendo Generation, and I really, really wish that someone had shown it to me

before I came-of-age. I think that it would have made me a little more at-peace with being single, and maybe a little more willing to ask myself some hard questions about my approach to the opposite sex.

In musicals, when emotion becomes too high onstage, the cast spontaneously bursts into song.

Scott Pilgrim does something similar, only with video games instead of music. But behind the

magical realism and plain old silliness, there's a lot of important questions about the baggage that each of us brings to a new relationship, and the ways in which our past romantic failures (whether they were our fault or not) makes it difficult, and sometimes impossible, to start afresh. But that's actually a

good thing, because if you forget your past mistakes, you won't be able to learn from them, and you'll just keep making the same mistakes over and over again.

7) Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood, by Marjane Satrapi

“In life you'll meet a lot of jerks. If they hurt you, tell yourself that it's because they're stupid. That will help keep you from reacting to their cruelty. Because there is nothing worse than bitterness and vengeance... Always keep your dignity and be true to yourself.”

― Marjane Satrapi

I'm abashed to admit that I never really gave much thought to Iran before reading this book. I pretty much just swallowed what the news told me without question: Iranians were crazy zealots who fund terrorists and jihadis and other unpleasant men with beards, and all they want is to see America burn. How ignorant I was.

Not only was Iran a pretty nice place to live before the

Islamic Revolution, women had more freedom in Iran than just about anywhere else in the region. Which made it all the harder for them to accept the veil, and the chaperone laws, and sending their sons and brothers off to become martyrs of their faith.

Persepolis made me wary (or at least aware) of the possibility that even in a prosperous and stable country, a small band of violent extremists can waltz in, play off the public's fears, and really eff things up for everyone else.

Discuss: Which graphic novel(s) do you feel have the potential to change my life? Tell me about them in the comments!