Sunday, August 14, 2016

Thoughts on Thrift Stores

In a way, thrift stores and secondhand shops are like museums of our collective failure to measure up against our own hopes and dreams; or of our failure to accurately predict what our hopes and dreams would be in the future. They collect the detritus of things we wanted, or thought we wanted, or others assumed we wanted: cheese knives and exercise equipment, ships in bottles and books on personal finance, cookbooks full of recipes ranging from faddish diets to diabetes-inducing confectionery. Tupperware sorted by color and shape, hand-painted porcelain Hummel figurines and row upon row upon row upon row of wine glasses. Aunt Mildred's fine china that we could never be bothered to wash by hand one the one night a year we would actually use it; good china that never got used at all; ugly, mismatched porcelain bowls we always hated but we were in college and poor and they worked alright so we couldn't just throw them away and buy new ones until after we graduated and could finally chuck the hideous things. Racks upon racks of t-shirts commemorating everything from the track teams of unfamiliar universities to cancer-walks. Jeans that we will never, ever fit into again no matter how hard we diet. Small forests of garish silk neckties, patterned to complement suit jackets which haven't been fashionable for twenty years. Eighty prints of the same T-shirt, donated by the local silkscreen shop due to a small-but-vital miscommunication with the client about what the shirts should actually say. Three dozen copies of a local rapper's debut album, each with liner notes hand-packed by his friends and family.

Labels:

thoughts on places

Friday, May 6, 2016

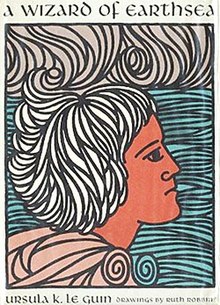

[Book Review] A Wizard of Earthsea (Ursula K. LeGuin, 1968)

The first thing I did upon waking this morning was pick up my recently-purchased copy of Ursula K. Le Guin's A Wizard of Earthsea and eagerly consume the remainder of the book, which I had read last night until I could no longer keep my eyes open.

I was in sixth grade when I first encountered this book in the school library. I changed school districts just after finishing the book, and the new school didn't have the other books in the series, so it gradually fell by the wayside and was forgotten. Until recently, when I saw a copy at the Dawn Treader and remembered really enjoying it the first time around. I'm really glad I bought it when I had the chance, because this book has reminded me of why I fell in love with fantasy in the first place, and its stunning power to enrich our lives with fresh perspective.

I think I may have been too young to really appreciate this book the first time around, because there's a lot going on here that I didn't notice the first time around. I must have completely failed to realize that Ged (a.k.a. Sparrowhawk, the main character) is not a white guy like virtually all fantasy protagonists (his skin tone is described as "red-brown"). I also failed to realize what a big deal that is, especially for a book published in 1968, when (as Le Guin herself said it) "everybody in science fiction had to be a honky named Bob or Joe or Bill."

I also feel like I'm finally old enough to really understand and absorb the lessons which the book teaches about patience, self-knowledge, and the responsibility which comes with great power (I just wish I had taken these lessons more to heart as a young man, rather than insisting on learning them for myself, the hard way). As the Archmage says to Ged after the young man's pride and hubris have left him gravely injured and loosed a terrible evil upon the world:

You thought, as a boy, that a mage is one who can do anything. So I thought, once. So did we all. And the truth is that as a man's real power grows and his knowledge widens, ever the way he can follow grows narrower: until at last he chooses nothing, but does only and wholly what he must do....I was also captivated by the lovingly-rendered descriptions of sea and surf and sky, of windswept moors and mist-hidden isles, narrow flotsam-choked inlets, great calm bays, and the endless, heaving waterscape of the Open Sea. Le Guin has an anthropologist's eye for culture and and a naturalist's eye for setting, and it makes me appreciate my own landscape (and the lake right behind my new house) all the more fully.

Tuesday, March 1, 2016

Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell

Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell, by Susanna Clarke (Bloomsbury, 2005)

It's not often that I wish a thousand-page novel could have been even longer. Rarer still is when I finish such a novel and immediately turn back to page one so I can start it over again. But that is exactly what I did with Susanna Clarke's masterful, eloquent, and exquisitely-constructed novel. By turns humorous and eerie, quotidian and otherworldly, Strange is already high on my list of all-time favorite books.

While no summary could really do justice to a novel of this size and complexity, here's a rundown: Magic has been dead in England for close to three centuries -- ever since the mysterious Raven King rode out of England and into Faerie -- until the secretive and reclusive Mr Gilbert Norrell resurrects the craft and becomes a celebrity overnight. Soon, one Jonathan Strange appears on the scene: a young gentleman with an intuitive gift for magic. Handsome, gregarious, and bold, Strange is everything Norrell is not. Together, they form an unlikely master-apprentice duo, and pool their considerable magical resources to aid England in its war against the dreaded Emperor Napoleon. But the friendship men so different as these cannot last forever: Norrell hoards information like a miser hoards gold, and Strange is drawn ever more strongly towards the mad, wild sorcery of the Raven King, widening the rift between teacher and pupil.

It's hard to know where to begin reviewing a work of this magnitude, but I suppose the most logical place to begin is the book's language, which is a pastiche of Georgian literary English (imagine a blend of Jane Austen and Mary Shelley, with a perhaps a splash of Charles Dickens). That might sound like it would be impenetrable, but the modern reader will have no difficulty there. As a matter of fact, it's much easier to read and understand than even Jane Austen, whose language was (in my opinion) uncommonly straightforward for her era. The peculiar spelling of some words ("chuse" instead of "choose," for instance) only adds to the impression that we are reading an actual document of the period, being written by someone who speaks the same language as the characters depicted.

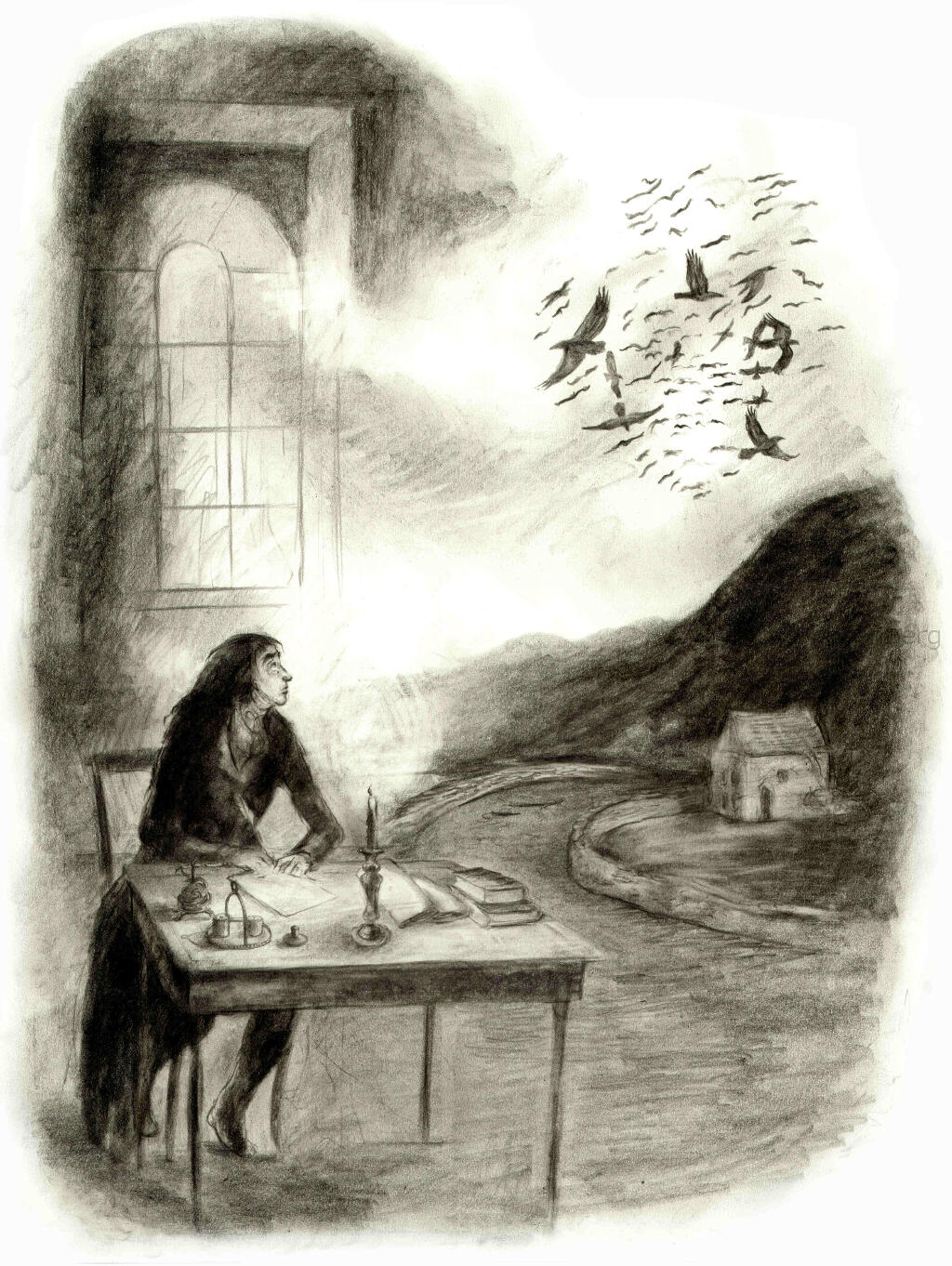

Portia Rosenberg's ghostly-grey illustrations lend the novel an atmosphere of gloomy magnificence. They bleed away from the gray illustration to a smoky nothingness, lacking a clear boundary, giving the impression that there is much more to this world which we only glimpse through a glass darkly.

Clarke does an excellent job of giving historical context to those who may not be great students of history, but as an American I found that there were many references to real historical events which I had heard of but, not knowing how they ultimately turned out, I was left unsure whether anything had been altered by the magicians' presence.

Oddly, it seems that even the presence of spectacular magic would change very little about the course of history. Even with two magicians and their scrying-dishes working full time on the war effort, Napoleon is continually outsmarting Britain's generals. It seems to me that, even if the gentleman's code of conduct prevents them from actually killing anyone, it should have been possible for them to cause some great personal tragedy to befall him, such as gout or an attack of hayfever.

But all of this is just nitpicking. Perhaps by making her alternate, magical history so similar to our own, Clarke is trying to show us that history has a vast momentum of its own, and that the presence of one or two men (even magicians) is not enough to entirely alter the course of history. Or maybe she's saying that our own history is just as magical and strange as this simulacrum she's created? Either way, Clarke's attention to historical detail is astonishing. Her inclusion of actual historical personages (such as King George III, Lord Byron, and Lord Wellington) shows a keen eye for historical psychology, and makes these normally distant, almost godlike figures, into real breathing humans, with whom we might take tea and conversation on a winter's day in northern England.

And speaking of the North: Clarke's love for northern England, in all its gloomy majesty, pervades every page of this book. Most Britons (especially northerners) love to joke/complain about how terrible and gloomy their weather is, but Clarke paints a loving portrait of windswept moors and grey winter hills, of darkling forests and white winter skies filled with cawing ravens.

The brown fields were partly flooded; they were strung with chains of chill, grey pools. The pattern of the pools had meaning. The pools had been written on to the fields by the rain. The pools were a magic worked by the rain, just as the tumbling of the black birds against the grey was a spell that the sky was working and the motion of grey-brown grasses was a spell that the wind made. Everything had meaning.

These are not the kind of images you would ever find in a travel brochure, but I find that they strike a chord deep within me: being from Michigan, her descriptions of wet, muddy earth and puddles reflecting pale grey skies has given me a new appreciation for the natural beauty of the place I live. I've noticed that after reading this book, I spend a lot more time looking at the sky and the landscape around me, and I just can't shake the feeling that, well... I'll just let Miss Clarke tell you in her own words:

This land is all too shallow

It is painted on the skyAnd trembles like the wind-swept rainWhen the Raven King goes by.

Friday, January 22, 2016

A Grammatical Grimoire

[Warning: I'm about to get all English-major up in here, so if you couldn't care less about grammar and punctuation, I suggest you get out now.]

It's always bothered me that "proper" style in English, according to unassailable sources such as the Purdue OWL and Strunk & White's The Elements of Style, is to place commas inside of quotation-marks, even when a comma was not present in the quoted text.

Using Hamlet's famous utterance as an example, here are a few "wrong" ways to quote a sentence...

...and the "right" way:

Note that the original sentence ("Alas, poor Yorick!") ends with an exclamation-point, not a comma. The sentence must be altered in order to make it fit with accepted citation style, and I've always taken exception to this rule.

It strikes me as strange, perhaps even a little dishonest, that style requires us to add punctuation where none existed in the original text. Granted, it's not a serious alteration to change a period or an exclamation-point to a comma, but it is a change nonetheless.

Quotation marks are supposed to signify a direct quotation, to tell the reader that the text quoted therein appears exactly as it appeared in the original source: word-for-word, letter-for letter, and character-for-character. Normally, even capitalization cannot be changed without making it clear that something in the text has been altered from its original form. For instance:

If we're not even supposed to change the capitalization of a single letter in any text we quote, then how can we justify changing where and whether the sentence appears to end? Not every sentence needs to be quoted from start to finish, but for people who are so anal-retentive about correctness and uniformity, it's very strange that English teachers are not just allowing, but commanding us to misquote our sources.

It's always bothered me that "proper" style in English, according to unassailable sources such as the Purdue OWL and Strunk & White's The Elements of Style, is to place commas inside of quotation-marks, even when a comma was not present in the quoted text.

Using Hamlet's famous utterance as an example, here are a few "wrong" ways to quote a sentence...

- "Alas, poor Yorick!" exclaimed Prince Hamlet.

- "Alas, poor Yorick", exclaimed Prince Hamlet.

- "Alas, poor Yorick" exclaimed Prince Hamlet.

...and the "right" way:

- "Alas, poor Yorick," exclaimed Prince Hamlet.

Note that the original sentence ("Alas, poor Yorick!") ends with an exclamation-point, not a comma. The sentence must be altered in order to make it fit with accepted citation style, and I've always taken exception to this rule.

It strikes me as strange, perhaps even a little dishonest, that style requires us to add punctuation where none existed in the original text. Granted, it's not a serious alteration to change a period or an exclamation-point to a comma, but it is a change nonetheless.

OK, Fry, you have a point. But hear me out!

Quotation marks are supposed to signify a direct quotation, to tell the reader that the text quoted therein appears exactly as it appeared in the original source: word-for-word, letter-for letter, and character-for-character. Normally, even capitalization cannot be changed without making it clear that something in the text has been altered from its original form. For instance:

- "[P]oor Yorick," as Hamlet calls him, was his late father's court-jester.

If we're not even supposed to change the capitalization of a single letter in any text we quote, then how can we justify changing where and whether the sentence appears to end? Not every sentence needs to be quoted from start to finish, but for people who are so anal-retentive about correctness and uniformity, it's very strange that English teachers are not just allowing, but commanding us to misquote our sources.

Wednesday, January 20, 2016

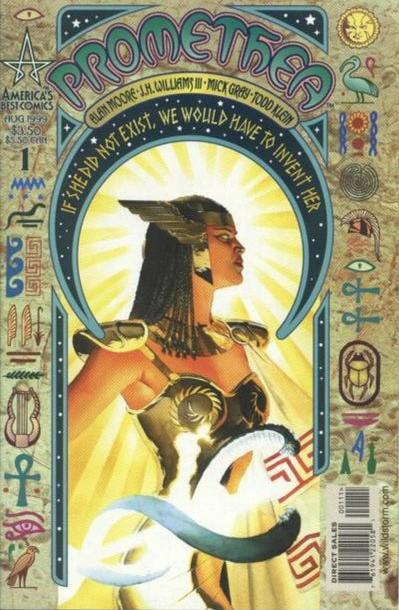

PROMETHEA, Volume 1

PROMETHEA, VOLUME 1 (issues 1-6)

Writer: Alan Moore

Artists: J.H. Williams III, Mick Gray, Charles Vess

Imagine a living story, penned and refined repeatedly and made flesh over the centuries by a long string of mortal "vessels," armed with the cleverness of Hermes and the wisdom of Thoth, and a bitchin' energy-caduceus for good measure: you now have a pretty accurate portrait of Promethea, the titular heroine of this extra-weird title from Alan Moore.

I'll admit that I was a little afraid (and reasonably so, I think) that Promethea was going to be little more than pseudo-mythological cheesecake. But somehow, despite having a male writer, a male artist, and wearing a bronze mid-thigh skirt and shoulder-baring bustier, Promethea feels like a legitimate icon of Mystical Femenine Strength. As Princess Diana of Themyscira has proven time and time again, a woman's taste in clothing is irrelevant to her ability to bust heads and kick asses, and I'm sorry I initially judged this particular book by its cover.

...though this alternate cover by Alex Ross IS pretty awesome-looking.

The story begins in Alexandria, Egypt, in 411 A.D. An old magician senses that a mob of religious extremists is coming to murder him. He tells his young daughter Promethea to flee into the desert, promising that "all my love and all my gods shall be about thee as a mantle." He then confronts the mob, and proceeds to use the Jedi Mind Trick to compel the mob to kill him. (lolwhut?) Who is this man, and why does he use his magic to seal his own doom? These questions remain tantalizingly unanswered during the first volume, but they do a great job of setting the tone for the rest of the tale. Right from the get-go, the author establishes that he is not going to spoon-feed us all of the answers; we're going to need to work for it.

Next, the narrative jumps ahead by about 1,600 years to New York city, just before the turn of the millennium. Sophie Bangs is a college student writing a term paper on Promethea, a character who seems to reappear in folklore and literature over the centuries, sometimes flowing from the pens of authors who could not possibly have been familiar with her previous incarnations. As is often the case with college students who investigate the supernatural, Sophie is soon swept up in a strange new world: one of ancient conspiracies, Goetic demons, Hermetic sorcery, Greco-Egyptian mysticism, living stories, a parallel universe composed of human thought and imagination, and at least one tearful, catchphrase-spouting gorilla.

Strangely, this panel makes perfect sense when read in context.

Not only does PROMETHEA, VOLUME 1 pass the Bechdel Test with flying colors, I'm pretty sure it actually fails the Reverse Bechdel Test: there's more than one male character in this book, but all of their conversations are solely about Promethea/Sophie and her various female helpers.

One of my favorite parts of PROMETHEA was the highly unorthodox layouts of the panels; I was particularly fond of the two-page spread in issue six which played out across the "panes" of the wings of a Mayan butterfly god. They're not space-efficient, but they make the reader constantly aware of the graphic nature of the tale, and they emphasize how Sophie's worldview is changing in dramatic and unexpected ways. And it's kind of cool that the artist is confident enough that he feels he doesn't need to use every square inch of space to tell the story, that he's willing to "take his time," so to speak.

Overall, PROMETHEA is a fascinating read for anyone with interest in literature, magic, and all things mystical. 18th-century poetry, trench-lore of WWI, pulp magazines of the 1920s, even "Little Nemo in Slumberland" all contribute to Promethea's constituent body of modern folklore; there's something here for everyone to enjoy. And of course, it's absolutely delicious to read. Most writers would struggle to meld such wildly different genres and formats into one narrative, but under Moore's guidance it seems only natural that these seemingly-disparate threads of story would be woven together into a cohesive whole.

This tale is deliciously weird, and I can't wait to find out where it goes next. Stay tuned for more info, Dear Reader; all my love and all my gods be as a mantle about thee.

You go, girl!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)