PROMETHEA, VOLUME 1 (issues 1-6)

Writer: Alan Moore

Artists: J.H. Williams III, Mick Gray, Charles Vess

Imagine a living story, penned and refined repeatedly and made flesh over the centuries by a long string of mortal "vessels," armed with the cleverness of Hermes and the wisdom of Thoth, and a bitchin' energy-

caduceus for good measure: you now have a pretty accurate portrait of Promethea, the titular heroine of this extra-weird title from Alan Moore.

I'll admit that I was a little afraid (and reasonably so, I think) that Promethea was going to be little more than pseudo-mythological cheesecake. But somehow, despite having a male writer, a male artist, and wearing a bronze mid-thigh skirt and shoulder-baring

bustier, Promethea feels like a legitimate icon of Mystical Femenine Strength. As

Princess Diana of Themyscira has proven time and time again, a woman's taste in clothing is irrelevant to her ability to bust heads and kick asses, and I'm sorry I initially judged this particular book by its cover.

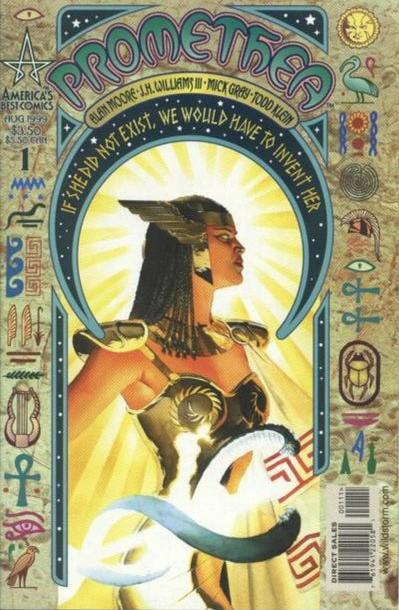

...though this alternate cover by Alex Ross IS pretty awesome-looking.

The story begins in Alexandria, Egypt, in 411 A.D. An old magician senses that a mob of religious extremists is coming to murder him. He tells his young daughter Promethea to flee into the desert, promising that "all my love and all my gods shall be about thee as a mantle." He then confronts the mob, and proceeds to use the Jedi Mind Trick

to compel the mob to kill him. (lolwhut?) Who is this man, and why does he use his magic to seal his own doom? These questions remain tantalizingly unanswered during the first volume, but they do a great job of setting the tone for the rest of the tale. Right from the get-go, the author establishes that he is not going to spoon-feed us all of the answers; we're going to need to work for it.

Next, the narrative jumps ahead by about 1,600 years to New York city, just before the turn of the millennium. Sophie Bangs is a college student writing a term paper on Promethea, a character who seems to reappear in folklore and literature over the centuries, sometimes flowing from the pens of authors who could not possibly have been familiar with her previous incarnations. As is often the case with college students who investigate the supernatural, Sophie is soon swept up in a strange new world: one of ancient conspiracies,

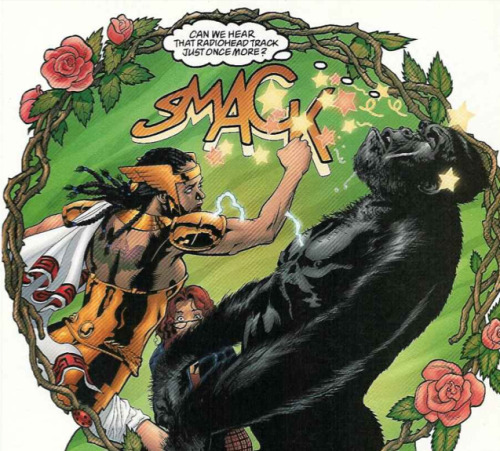

Goetic demons, Hermetic sorcery, Greco-Egyptian mysticism, living stories, a parallel universe composed of human thought and imagination, and at least one tearful, catchphrase-spouting gorilla.

Strangely, this panel makes perfect sense when read in context.

Not only does PROMETHEA, VOLUME 1 pass the

Bechdel Test with flying colors, I'm pretty sure it actually

fails the Reverse Bechdel Test: there's more than one male character in this book, but all of their conversations are solely about Promethea/Sophie and her various female helpers.

Moore can get metaphysical at times, even mystical, but it never feels like he's preaching; we're free to ignore this strange new worldview, or incorporate it into our paradigm, as we see fit. For instance: at one point, a previous incarnation of Prometha takes our heroine aside to show her the different layers/levels of reality, progressing from solid matter to emotions to thought and reason to the soul and beyond. In the hands of a less-talented author, this kind of unabashed philosophizing would come off as preachy (or worse, goofy New Age mumbo-jumbo). But under Moore's skilled direction, it gains real literary heft. It doesn't feel like he's talking to the reader, we're just watching one incarnation of Promethea speaking with another, free from proselytizing on the author's part.

One of my favorite parts of PROMETHEA was the highly unorthodox layouts of the panels; I was particularly fond of the two-page spread in issue six which played out across the "panes" of the wings of a Mayan butterfly god. They're not space-efficient, but they make the reader constantly aware of the graphic nature of the tale, and they emphasize how Sophie's worldview is changing in dramatic and unexpected ways. And it's kind of cool that the artist is confident enough that he feels he doesn't need to use every square inch of space to tell the story, that he's willing to "take his time," so to speak.

Overall, PROMETHEA is a fascinating read for anyone with interest in literature, magic, and all things mystical. 18th-century poetry, trench-lore of WWI, pulp magazines of the 1920s, even "

Little Nemo in Slumberland" all contribute to Promethea's constituent body of modern folklore; there's something here for everyone to enjoy. And of course, it's absolutely delicious to read. Most writers would struggle to meld such wildly different genres and formats into one narrative, but under Moore's guidance it seems only natural that these seemingly-disparate threads of story would be woven together into a cohesive whole.

This tale is deliciously weird, and I can't wait to find out where it goes next. Stay tuned for more info, Dear Reader; all my love and all my gods be as a mantle about thee.

You go, girl!