Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell, by Susanna Clarke (Bloomsbury, 2005)

It's not often that I wish a thousand-page novel could have been even longer. Rarer still is when I finish such a novel and immediately turn back to page one so I can start it over again. But that is exactly what I did with Susanna Clarke's masterful, eloquent, and exquisitely-constructed novel. By turns humorous and eerie, quotidian and otherworldly, Strange is already high on my list of all-time favorite books.

While no summary could really do justice to a novel of this size and complexity, here's a rundown: Magic has been dead in England for close to three centuries -- ever since the mysterious Raven King rode out of England and into Faerie -- until the secretive and reclusive Mr Gilbert Norrell resurrects the craft and becomes a celebrity overnight. Soon, one Jonathan Strange appears on the scene: a young gentleman with an intuitive gift for magic. Handsome, gregarious, and bold, Strange is everything Norrell is not. Together, they form an unlikely master-apprentice duo, and pool their considerable magical resources to aid England in its war against the dreaded Emperor Napoleon. But the friendship men so different as these cannot last forever: Norrell hoards information like a miser hoards gold, and Strange is drawn ever more strongly towards the mad, wild sorcery of the Raven King, widening the rift between teacher and pupil.

It's hard to know where to begin reviewing a work of this magnitude, but I suppose the most logical place to begin is the book's language, which is a pastiche of Georgian literary English (imagine a blend of Jane Austen and Mary Shelley, with a perhaps a splash of Charles Dickens). That might sound like it would be impenetrable, but the modern reader will have no difficulty there. As a matter of fact, it's much easier to read and understand than even Jane Austen, whose language was (in my opinion) uncommonly straightforward for her era. The peculiar spelling of some words ("chuse" instead of "choose," for instance) only adds to the impression that we are reading an actual document of the period, being written by someone who speaks the same language as the characters depicted.

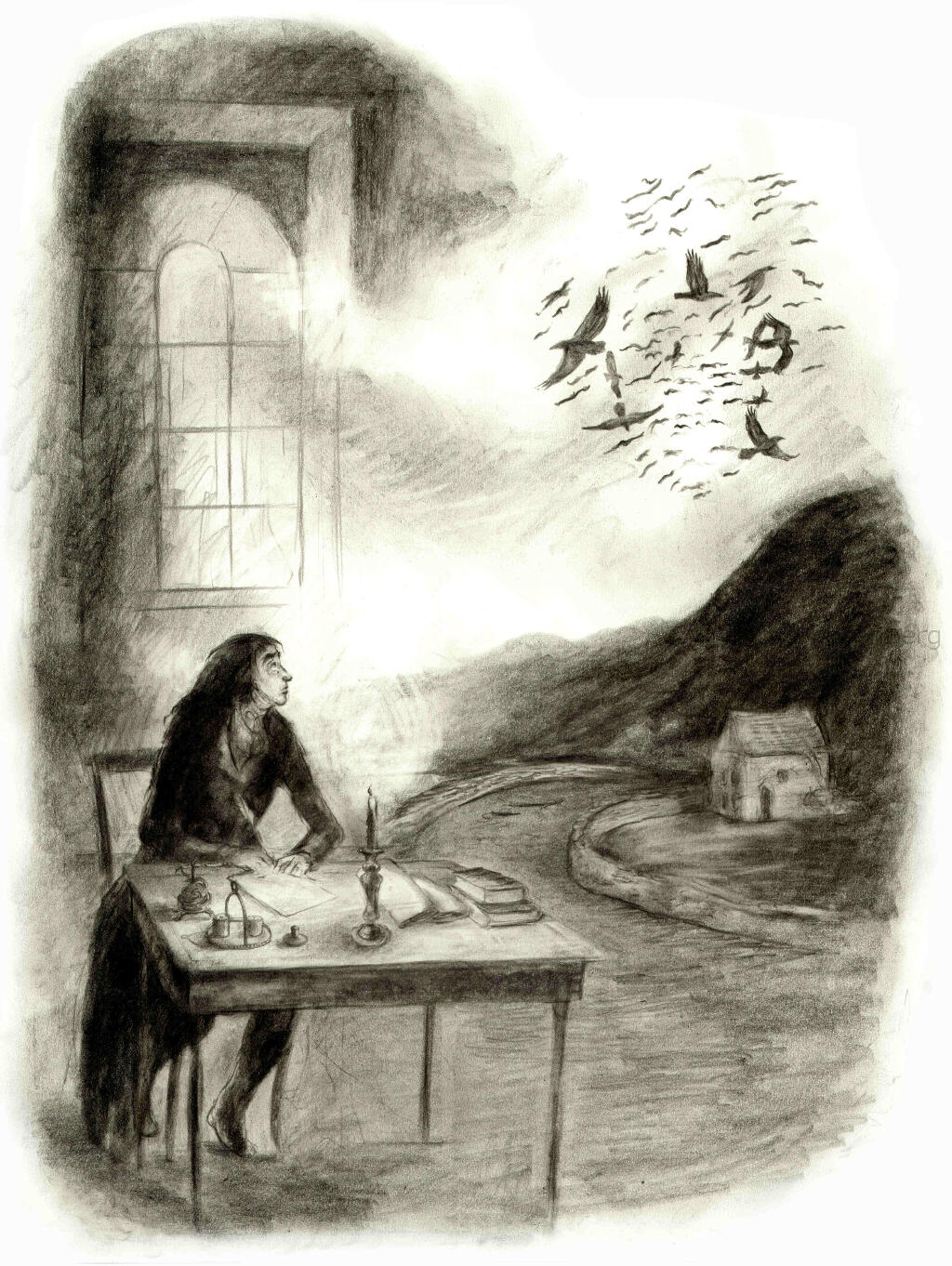

Portia Rosenberg's ghostly-grey illustrations lend the novel an atmosphere of gloomy magnificence. They bleed away from the gray illustration to a smoky nothingness, lacking a clear boundary, giving the impression that there is much more to this world which we only glimpse through a glass darkly.

Clarke does an excellent job of giving historical context to those who may not be great students of history, but as an American I found that there were many references to real historical events which I had heard of but, not knowing how they ultimately turned out, I was left unsure whether anything had been altered by the magicians' presence.

Oddly, it seems that even the presence of spectacular magic would change very little about the course of history. Even with two magicians and their scrying-dishes working full time on the war effort, Napoleon is continually outsmarting Britain's generals. It seems to me that, even if the gentleman's code of conduct prevents them from actually killing anyone, it should have been possible for them to cause some great personal tragedy to befall him, such as gout or an attack of hayfever.

But all of this is just nitpicking. Perhaps by making her alternate, magical history so similar to our own, Clarke is trying to show us that history has a vast momentum of its own, and that the presence of one or two men (even magicians) is not enough to entirely alter the course of history. Or maybe she's saying that our own history is just as magical and strange as this simulacrum she's created? Either way, Clarke's attention to historical detail is astonishing. Her inclusion of actual historical personages (such as King George III, Lord Byron, and Lord Wellington) shows a keen eye for historical psychology, and makes these normally distant, almost godlike figures, into real breathing humans, with whom we might take tea and conversation on a winter's day in northern England.

And speaking of the North: Clarke's love for northern England, in all its gloomy majesty, pervades every page of this book. Most Britons (especially northerners) love to joke/complain about how terrible and gloomy their weather is, but Clarke paints a loving portrait of windswept moors and grey winter hills, of darkling forests and white winter skies filled with cawing ravens.

The brown fields were partly flooded; they were strung with chains of chill, grey pools. The pattern of the pools had meaning. The pools had been written on to the fields by the rain. The pools were a magic worked by the rain, just as the tumbling of the black birds against the grey was a spell that the sky was working and the motion of grey-brown grasses was a spell that the wind made. Everything had meaning.

These are not the kind of images you would ever find in a travel brochure, but I find that they strike a chord deep within me: being from Michigan, her descriptions of wet, muddy earth and puddles reflecting pale grey skies has given me a new appreciation for the natural beauty of the place I live. I've noticed that after reading this book, I spend a lot more time looking at the sky and the landscape around me, and I just can't shake the feeling that, well... I'll just let Miss Clarke tell you in her own words:

This land is all too shallow

It is painted on the skyAnd trembles like the wind-swept rainWhen the Raven King goes by.

You definitely piqued my interest--I'll have to go back to my copy and try reading it again! It's unfortunate that the book is so large one doesn't particularly want to haul it around everywhere it might have a chance of being read.

ReplyDeleteIf you're interested in the idea of History as its own force, and the idea of what channels it might flow through, and what effect individuals might have on those channels, I'd recommend reading Connie Willis's "To Say Nothing of The Dog," a tale of time travel, history, and hilarity.